Running in Morocco Taught Me an Invaluable Lesson

(Photo: Courtesy Rogue Expeditions)

On a cool Sunday morning in late February, my feet lumber across a rocky trail cradled by rugged auburn hills as far as the eye can see. I’m seven miles into this run when I see a man, wrapped in a cobalt turban, sitting on a donkey. The traditional cloth helps protect against wind and sun. It covers his head and mouth, revealing only his chestnut-colored eyes. As we exchange curious glances, he nods and extends a hand to greet me.

I’m in Berber territory here in the eerily quiet Dades Valley, which sits at 5,200 feet above sea level. It’s my third day of running through the High Atlas Mountains of central Morocco. And I’ve come face-to-face with a nomad of the Sahara.

There is no accurate account of this tribe, the indigenous inhabitants of Northern Africa who have lived here nomadically, intertwined with the land, for thousands of years. In Morocco, Berbers are known to migrate from the unbearable heat of the Sahara—where temperatures can soar to an intolerable 120-degrees Fahrenheit in the summer—to the cooler 70-degree air of the High Atlas, the highest mountain range in North Africa. Later, I am told that this man was likely on his way to the market. It’s typically a bi-monthly journey when decamped in the mountains, and it can take a few hours round trip by donkey.

Similar Reads

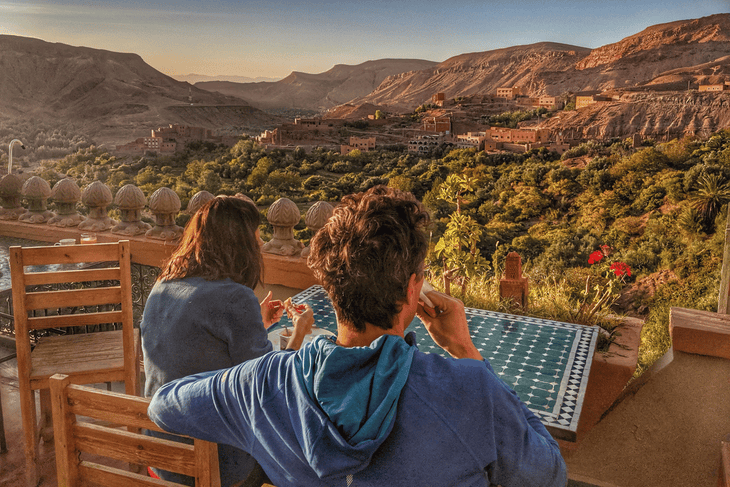

I contemplate this encounter after the run while sitting on the terracotta-colored patio at a hotel in Tinghir, a city of 42,000 in the Todra Valley. My hair dripping wet under the late-afternoon sun, a whiff of freshly peeled clementines momentarily distracts from the soreness emanating from my IT bands, which are feeling the wrath of running down the steep hills.

Though I’ve already logged 30 miles, I’m only halfway into this week-long running pilgrimage in Morocco, organized by Rogue Expeditions, a U.S. adventure travel company that specializes in international running tours—and apparently Type-2 fun.

A Challenge for All

My trip in Morocco highlights the massive and impressive jagged gorges and wide-sweeping rocky trails of the High Atlas, which stretch over 600 miles diagonally across the country. This journey, which involves driving 700 miles across 10 days, will bring us to run amid the expansive towering dunes of the Sahara, the world’s largest hot desert, and the third-largest desert overall.

As I read Rogue’s digital brochure for “Run Morocco,” the description for the runs—upwards of 11 miles daily (and half of them at altitude)—seemed hardcore. But the trip also sounded like an irresistible way to get to know the country’s colorful and diverse landscapes that include the emerald green Ounila Valley, full of ancient remote villages, and the desiccated Lake Iriki, reportedly once the second-largest lake in Africa.

Though the mileage for this trip could be considered relatively intimidating, similarly to other Rogue Expeditions trips, runners of all abilities are accommodated. I’m assured by the two lead guides, Alain Pernau, an ultrarunner from Chile, and Kara Folkerts, a seasoned trail runner and yoga teacher from Canada, that a support vehicle would be available during every run should any of us opt to cut some miles.

Joining us are eight other runners from the U.S., including a married couple from New York City, a chemist from Atlanta, and a doctor who lives in Houston. Half of the participants are repeat clients, several in their mid-to-late 40s.

“I’ve always had the feeling that you’re included, you’re accepted, and you’re not judged,” one self-described introverted repeat client, 59, tells me. “It’s a really good format for solo travelers, especially if you’re a woman.”

Later, I overhear a participant tell another, “These trips are life changing.” I begin to understand this when I meet Hamid, the man who helped inspire the existence of this Morocco running tour. He got his start in tourism as a teen, camel trekking before he dropped out of high school to work full time in tourism. In Morocco, the tourism sector is a key economic driver that accounts for over $10.5 billion in revenue annually. For Hamid, 39, working in the industry has helped finance his six siblings through college.

“I’m very proud of that,” he says, adding that over the past few years he also managed to save enough to finally send his parents to the holy city of Mecca in Saudi Arabia for the annual Islamic pilgrimage, known as Hajj. As one of the five pillars of Islam, it is required of every Muslim with the means to afford it.

Hamid, I also discover, is blessed with a natural sense of direction, never once relying on GPS, but rather navigating the crevices of the country with what he jokingly refers to as “BPS.”

“Berber Positioning System,” he clarifies, chuckling as he bobs his head to the beat of traditional Moroccan music blasting through the car stereo. “We just know the way.”

Off the Beaten Path

I awake the next morning, still in the thin air of the mountains, wearing my fleece jacket. Holding a hot cup of bitter-tasting black coffee helps me warm up while I fuel for the upcoming run with a sfinge, a doughy fritter, which I slather with butter and jam. Moroccan breakfasts are typically carb-heavy, with various breads complemented with olives, yogurt, and freshly-squeezed orange juice—delicious, but not exactly stomach-friendly before a long run.

Today we head to the Todra Gorges, Morocco’s premier climbing destination and a popular sightseeing attraction, as evidenced by an influx of sprinter vans toting European tourists. We begin the 11-mile run at the top of an asphalt road that zig-zags down into the gorges before finishing back at our hotel in a kasbah, an ancient fortress. Pernau tells the group that the route, which is predominately shaded, is “great for cruise mode.”

And even though it’s mostly downhill, my IT bands feel too tight to be running on a hard surface. As I run, a breeze picks up, stirring the surrounding almond blossoms and olive trees. This vegetation seems to hug every corner of the country, from major cities like Marrakech to remote villages.

One moment I hear a customary Islamic Adhan, the call to prayer which occurs five times a day, and the next I spot garbage littered everywhere, the air punctured with the scent of burning plastic. It’s an odd juxtaposition amid donkeys loaded with supplies and children standing at the ready to high-five passersby.

Our next venture, south into the Draa Valley, showcases the lifeblood of the region, an oasis of 4.5 million date palms. Dates are particularly important in Moroccan culture. Not only are they shared during communal meals, they also hold spiritual significance during the holy month of Ramadan, when the fruit is commonly eaten to break the fast. It is just after this brief stopping point that we reach a guesthouse in the city of Zagora, along the route to the Sahara, for a much-needed rest day.

With no run on the agenda, the following day we head to a local pottery cooperative to learn about Morocco’s rich heritage in artisan ceramics. I watch a craftsman spin a mound of clay sourced from the Draa river-bed, shaping small bowls that will later be glazed using natural minerals to color it a striking emerald green. Just as he does with each four-hour shift, his body is nestled halfway underground as a way to stay cool in the heat while he works.

Zen and the Art of Moroccan Magic

Late morning on day seven, we travel to Hamid’s family home in M’Hamid, a village of roughly 7,500 inhabitants. Here is one of two places where the road ends, or rather turns into a carpet of sand merging into the Sahara.

We are greeted by his mother and his younger sister as they usher us into a room, the floor of which is lined with timeworn handmade carpets. One by one, Hamid’s mother begins to pour a kettle of mint tea, her hand two feet above each glass. It’s said the higher the pour, the more respect paid to the recipient. The tea is complemented by what Hamid refers to as Berber pizza, a round-shaped bread seasoned with a blend of spices that include cumin and paprika. It’s a final top off before attempting to run 11 miles at noon in the hot breath of the Sahara.

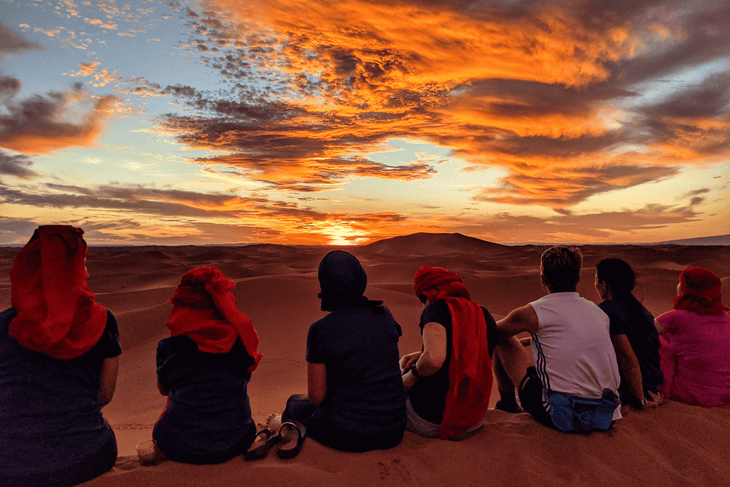

To prepare for the journey, Hamid wraps my head in a red scarf as protection from the scathing hot sun. One by one, each participant receives their own scarf, which Hamid refers to as “the Berber stamp.”

Having run in the Kalahari and Namib deserts in Namibia last April, I am quickly reminded that there is no graceful way to conquer the sand. It is awkward and slippery, yet oddly a happy frustration, much like the bumpy drive to arrive here.

This desert run is like a hot, slow-motion version of a boot camp. My stride shortens so much that I’m more so marching as opposed to running. It is a humble reminder that there are many ways to experience running—and slowing down is one of them.

With each calculated step, I marvel at the shamrock green flora, the result of more than a year’s worth of rain that fell in two days last October. I feel every crevice of my trail shoes loaded with a gritty consequence by the time I reach the finishing point, a desert camp where we will sleep for the night.

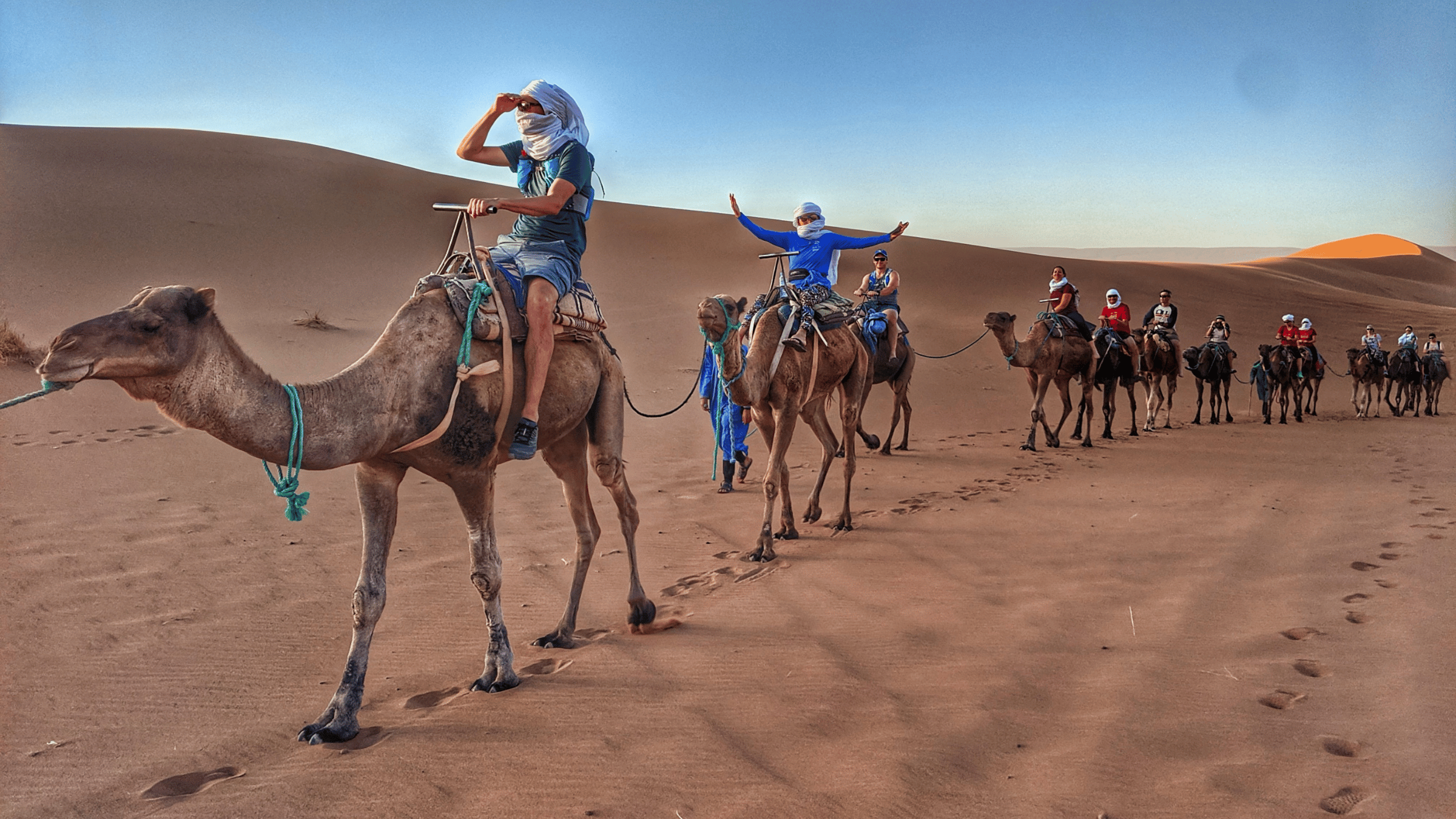

It is here, hours after the run, that we are escorted on zen-like dromedaries, the sun finally no longer slapping our faces, as we are deposited at the base of a dune. We climb to the top, slipping and chuckling on the way up, before we are met with a melody of pinks melting into the horizon. As a bottle of wine is passed around, I quietly toast to the art of slowing down.